We love all of our rugs like we love our own children. But, like children, there are some that have been hanging around too long, and you just want them to get the hell out of your house.

On August 30, Mellah sent senior correspondent John Honeyman from Toronto, Canada to Marrakesh, Morocco on a rug buying trip. Over the next 4 weeks Mellah will be publishing his dispatches from the cities and souks of Morocco. See below for Part 4 or click here for part 1, here for part 2, and here for part 3.

Eid Mubarak

Sidi Kouaki was a welcome break, and both my and Mustapha's energy levels are restored. The dusty plains on the way back to Marrakesh don't look as dry, as desolate as they had on the drive there just 2 days ago. It is a couple days before Eid, and there is more traffic, much of it hatchbacks and pickup trucks transporting alarmed looking lambs to slaughter. I am eager to return to Marrakesh and close the deals with Choukri. We must make arrangements with Adil, the transitaire to get the Moroccan rugs back to Toronto. The rugs need to get to Toronto. I need to get to Toronto.

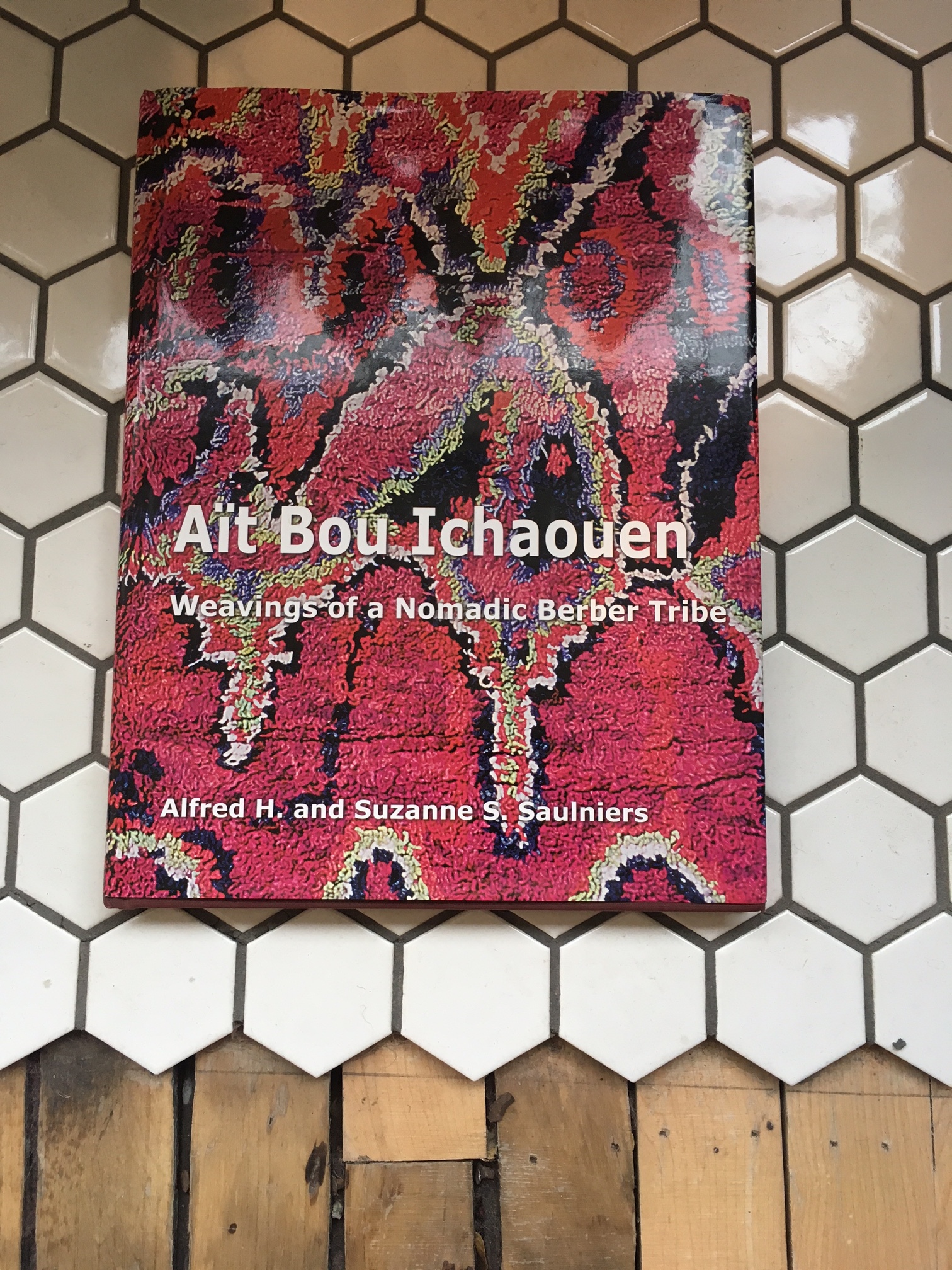

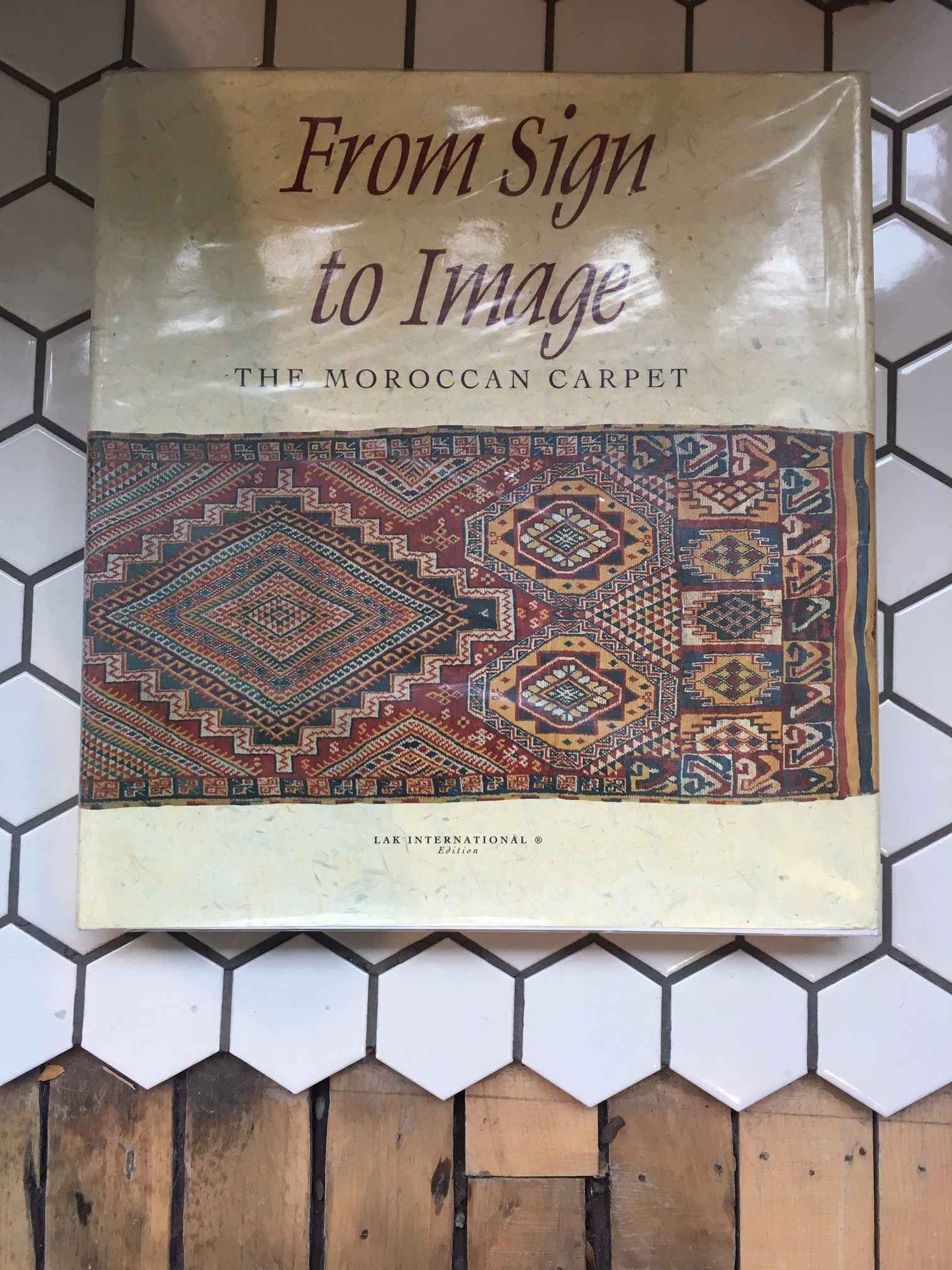

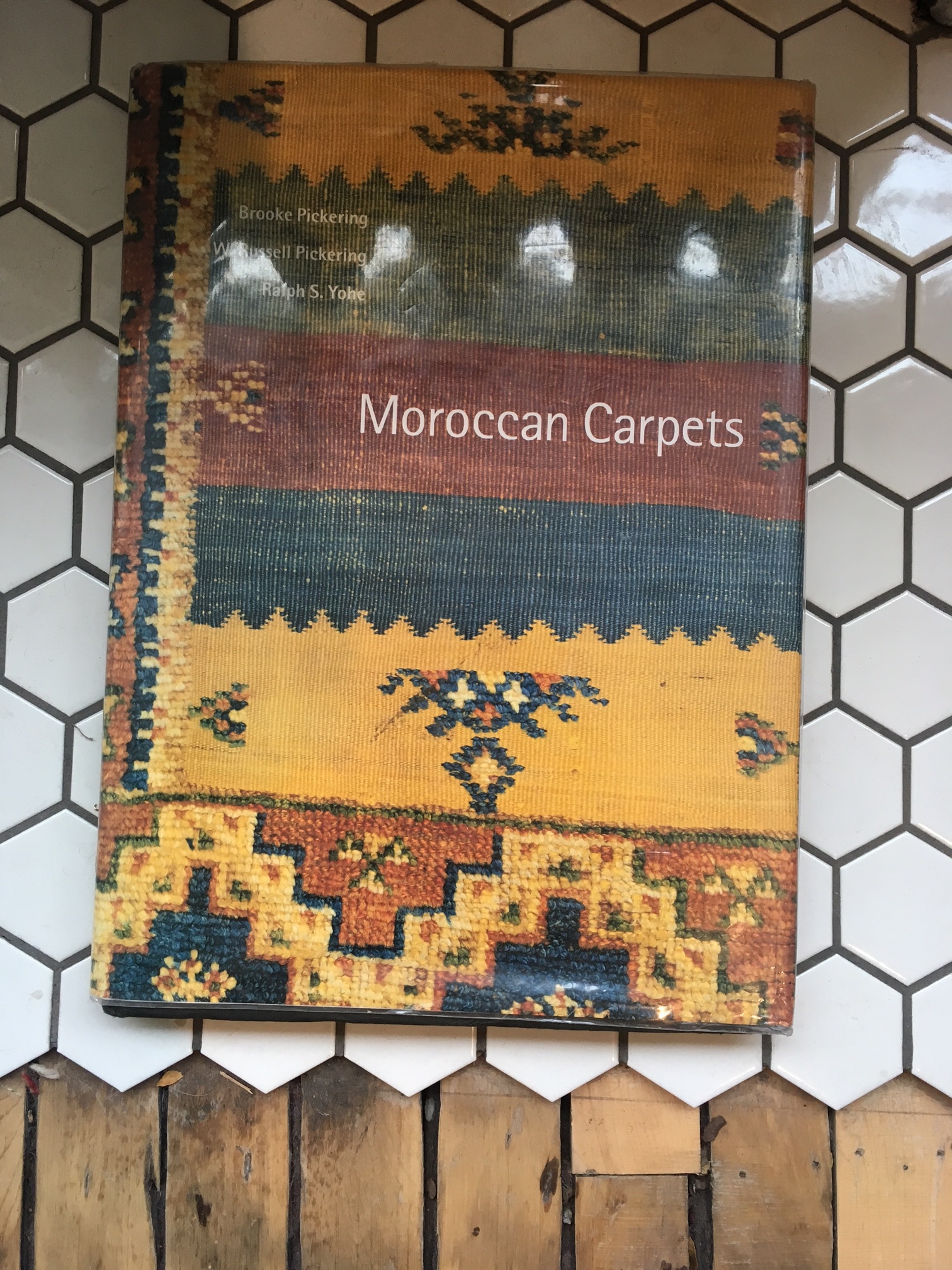

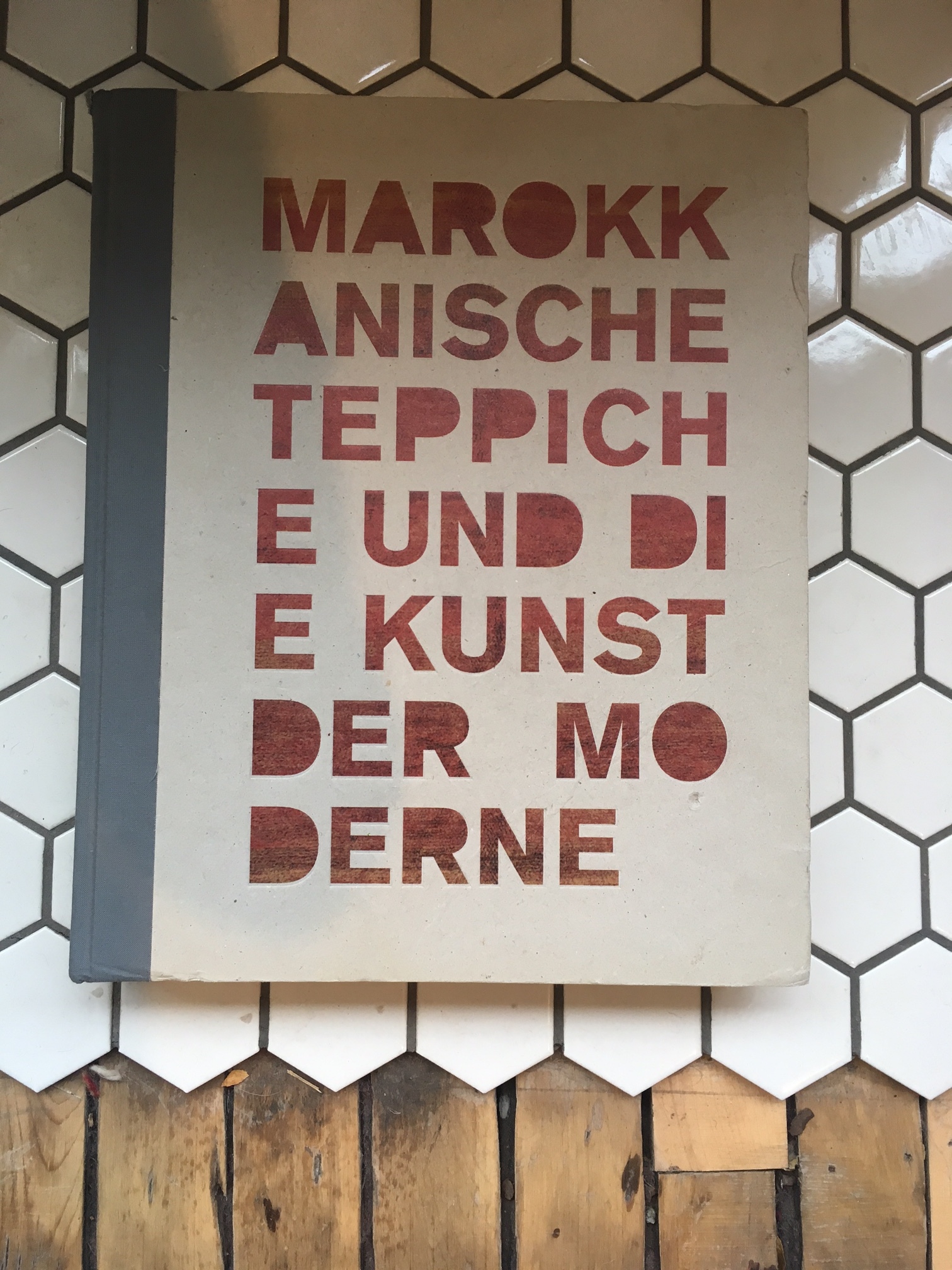

Marrakesh is sunny and festive feeling. Many people are returning to the hometowns and villages for the holiday, so the roads leaving town are busy. Eid is a holiday taken seriously, and many shops and businesses are closed, which feels very strange in Marrakesh—a busy and commerce-driven city. We stop by Mustapha's mother's apartment so he can deliver her some fruit he bought at a roadside stand. When he returns, we have lunch at a hotel where his brother works. We make it back to Mustapha's apartment in the Gueliz and his houseman goes to the Carrefour to buy us some beer. We spend the rest of the afternoon hanging out and looking through German language books about Berber weaving.

That night we meet a few of Mustapha's friends at a Tapas bar in the Hivernage, a fancy and Europeanized neighborhood between the Gueliz and the Medina. Mustapha's Scottish-Moroccan cousin and and his Bulgarian lounge-singer girlfriend suggest we go to a club a little outside of town. The bouncers let us in. We secure a table and order bottle service. I see Choukri's two boys, the students at University of Ottawa, at a table with a large group of girls. They are mortified to see Mustapha, who is in his mid forties, and try to hide from us. Mustapha—who knows no shame—rushes over to their table to greet them. We tire of the club and drive home on an empty tank of gas.

Da Club.

Choukri calls me the next day to inspect the vintage Moroccan rugs he has repaired. One of his m'taalams picks me up at Mustapha's apartment on a tiny motorbike. He has a helmet for himself but not for me. There is nowhere to hang onto the bike, so I hold him around his waist. It is now the day before Eid and Marrakesh is a ghost town. Choukri shows me the repaired rugs and all looks satisfactory. We shake hands, and the Moroccan rugs are packed. He sends his men home for the holiday and we say goodbye. He promises to come to Toronto and visit the shop in the spring. The m'taalam takes me back to Mustapha's. It is my last night, and we go to Mamma Mia, an Italian restaurant at which Mustapha is a regular. He speaks to the host in perfect Italian, and we are seated at his regular table in the back. We eat pasta, drink La Cuvée du Terroir, and talk about our plans for the next day. I have booked a hotel at the Casablanca airport, where I have a flight leaving for Montreal early the following morning. He has kept the rental car and will drive me the two hours to Casablanca. I offer to take the train, telling him he has been so generous and it is not necessary, but he insists.

Choukri's son comes by the apartment in the morning. He will be joining us on the drive. We get on the toll road north to Casablanca and listen to loud techno music the whole way. We get off the highway and again I must stop at an ATM to give Mustapha more cash for a few additional rugs I selected from his personal collection. We try a few before we find one that will let me withdraw money; I get the feeling Mustapha thinks I am trying to pull a fast one on him. I finally get the money and give it to Mustapha. We arrive at the airport hotel in Casablanca, give each other a hug and kisses on each cheek. We say long goodbyes, talking of future plans for Mustapha to come to Toronto in the spring and do a Berber art exhibition at Mellah. I smile when I imagine him speaking in his German/Moroccan accent, passionately presenting his unique Moroccan treasures with equal measures scholarship and shenanigans. Mustapha has treated me well—as a business partner and as a friend—and I am grateful.

For the first time in two weeks, I am alone. Mustapha's apartment didn't have a shower. Not because Mustapha is poor (he isn't), rather because he is both bohemian and lazy and doesn't own a shower head. You have to dump buckets of cold water on your head and body while trying to soap up. It's tricky and not very effective. I linger in the hot shower, get out and watch French TV in the air-conditioned room with a towel around my waist. I start to get hungry for dinner, so I get dressed and realize that I am missing my wallet. I ransack my luggage but cannot find it.I have 100 dirhams, which is enough for dinner, but not enough to get me from Montreal to Toronto after the flight. Panicking, I pick up the phone and call the one person I know: Daddy. Mustapha picks up on the first ring. He and Choukri's son are on the road back to Marrakesh. I left my wallet in the back seat after going to one of the many ATMs to pay Mustapha. He quickly devises a plan whereby he will send a man in a car the next morning at 6:30, the day of Eid, and a scant one hour before I have to be at the airport to catch my flight to Montreal. Mustapha, in one final act of kindness, will pay. I don't sleep well. I go down to the lobby at 6:15 and the man with my wallet is already there. He is friendly but does not speak English or French, so it is hard to convey how thankful I am. I offer him the 50 dirhams I have left, which he declines. I say shokran and Eid Mubarak. He smiles and walks away.

*****

It's easy when you work in the rug business to start thinking of rugs as inventory, as goods and chattels. You obsess over how many you have, how many you need, anticipating what people will want. You talk about them, you show them, you photograph them, you Instagram them, you unfold them and you fold them back up again. You get sick of some, you wonder why some aren't selling, you love your clients' taste, you hate your clients' taste, you hate your own taste. You try to sell the rugs, these handicrafts that have been labored over for months, family heirlooms that have been in homes for years, become mere things, commodities. You also can't go too far the other way and mystify them too much, orientalize them. They are made by other human beings, and they are beautiful, yes, but they are not magic. Berber rugs are proletarian, folk art. Artisans lacking formal technical skills weave them for practical reasons, made them the way the know how, and have been doing for thousands of years. It is we who imbue them monetary value. There is a lot of marketing malarkey around imported handicraft businesses, the social enterprise aspect of it, at least. Each object has a story, but often that story is that someone sold something in her home to buy cooking gas, or pay her cellphone bill, or to send her kid to school. Objects don't have stories. People have stories.

On August 30, Mellah sent senior correspondent John Honeyman from Toronto, Canada to Marrakesh, Morocco on a rug buying trip. Over the next 4 weeks Mellah will be publishing his dispatches from the cities and souks of Morocco. See below for Part 3 or click here for part 1, here for part 2.

THE ROAD TO ESSAOUIRA

Mustafa has a different rental Dacia Logan now, this time a diesel model in forest green. The gas light has been on since we got it from the rental agency outside Mustafa's apartment, but it doesn't perturb him much. He smokes and talks on his cell phone while driving 120 kilometers an hour on a road with a speed limit of 60. He weaves through the ubiquitous donkeys and motorbikes, swearing and making obscene hand gestures at other drivers. His particular brand of road rage is funny: he needs to instruct as much as berate. Each transgression is a teachable moment in acid-tongued Arabic. The offenders are made acutely aware of how they are fucking up, and they appear both bemused and chastened. This all fits into what I dub Mustafa's "daddy complex." We have taken on semi-serious nicknames of "Buddy" and "Daddy." Daddy is the wise, all powerful leader, while Buddy is the acquiescent and impotent patsy who has taken the backseat to Daddy's whims. Daddy sets every day's agenda, rents the cars, buys the food and deals with the vendors in Arabic. At the best of times, transparency is not a core competency of Moroccan rug dealers—in fact they thrive and profit from the information deficit between themselves and the buyers. Mustafa takes this opacity to near Nixonian levels. I cede control and autonomy via this confidence sapping and demeaning arrangement, but I also welcome it. I no longer feel like an experienced traveler, a business owner and a father; I feel like a mute with a wallet ready to be fed and transported by my wise and benevolent daddy. We joke about it, but like any joke worth laughing at, it is also mainly true: the nicknames are accurate. We pull into a gas station just as the car is about to die and Mustafa puts in ten liters, even though 200 kilometers remain on our trip to the coast. He puts the gas in the car while I sit and read the newspaper on my phone. He pays, naturally.

Marrakesh was hot. Like, really hot. Every day was at least 45 degrees, cloudy, and humid. Moroccans opened conversations with weather woes, similar to Canadians in the dead of winter. It had been exhausting choosing the rugs from Choukri's store, and I was desperate to get to the coast for cooler temperatures. We needed to leave and Mustafa was happy to take me.

The plains outside of Marrakesh are dry and desolate, only occasionally punctuated by towns and palm oases. There are scrubby argan trees along the side of the highway, whose kernels are harvested to make oil for food and beauty products. Goats like to eat the nuts straight from the source, and climb the trees to the get them. Goatherds are happy to take a few dirhams from tourists for photos. There are a few cities, the most notable being Chichaoua, famous for its eponymous monochromatic red rugs. Mustafa and I stop in Chichaoua for fried chicken and so I can make several withdrawals from an ATM to settle a deal we had made in Marrakesh for wedding blankets. I am surprised that my bank in Canada allows this. I give Mustafa his 8000 dirhams. Buddy is fed and Daddy is rich.

We arrive in Sidi Kaouki, a small seaside town 13 kilometers from Essaouira. The air is cooler, and the villa that Mustafa has rented is comfortable and clean. There are a few restaurants, guests houses and surf shops along the coast, and surfers—both Moroccan and tourists—bob just past the breakers. Groups of Moroccan boys play soccer on the beach and guides snooze against their idle camels. I observe all this from the patio of our villa. The heat and hustle of Marrakesh has exhausted me, and I'm content to sit in a comfortable chair and look at the Atlantic ocean, grateful that I am not in a carpet shop. Mustafa gets bored and disappears with the Logan while I return inside in search of English satellite TV channels . I find a children's movie and nod off for a little.

The sunset view from our villa in Sidi Kaouki.

Mustafa returns with cold beer, white wine, two tagines, and a greasy paper bag of fried shrimp and calamari. The mood has lifted. We have been spending too much time with each other— especially because we don't know each other that well—and the latent transactional character of our relationship has made the vibe a little terse and awkward at times. We eat and drink on the patio and talk about our families. Mustafa has two little girls who live in Germany and he misses them greatly. They are homeschooled and live on an organic farm with his German wife, and come to Marrakesh only a few times a year. Mustafa hustles hard to make money to support them, and he never stops working. Even as we eat he conducts business on his phone, which, like mine, has as many pictures of rugs as it does of his children.

Takeaway, Moroccan style. No disposable dishes here—we returned the clay tagines the next day.

The next day we drive to Essaouira. By now, I am used to Mustafa's driving and it doesn't phase me as he accelerates to 120 kilometers an hour in blind curves on a narrow road. I scoff at the gas light. The air feels wonderful and I am excited to go to Essaouira, a very relaxed city by Moroccan standards. We walk by the main harbor where the fishing boats are docked. Stray cats and gulls compete for fish remnants and fishermen bring in the day's catch. We stroll through the main square on our way to get soup at Mustafa's friend's restaurant. Along the way Mustafa upbraids a man for mistreating a donkey, admonishes some kids for getting too close to us while they're playing soccer, and gives money to every single beggar we see. Like in Marrakesh, Mustafa knows everyone; it is impossible to walk more than a few meters before he stops to greet friends with the double cheek kiss and longer-than-casual conversations. We eat soup, buy some argan oil, and go to Patisserie Driss for coffee and pain au chocolat before we return to our patio, satellite TV, and swimming pool in Sidi Kaouki. The respite has been welcome, but there is still much work to do in Marrakesh, and Mustafa and I are getting antsy.