On August 30, Mellah sent senior correspondent John Honeyman from Toronto, Canada to Marrakesh, Morocco on a rug buying trip. Over the next 4 weeks Mellah will be publishing his dispatches from the cities and souks of Morocco. See below for Part 4 or click here for part 1, here for part 2, and here for part 3.

Eid Mubarak

Sidi Kouaki was a welcome break, and both my and Mustapha's energy levels are restored. The dusty plains on the way back to Marrakesh don't look as dry, as desolate as they had on the drive there just 2 days ago. It is a couple days before Eid, and there is more traffic, much of it hatchbacks and pickup trucks transporting alarmed looking lambs to slaughter. I am eager to return to Marrakesh and close the deals with Choukri. We must make arrangements with Adil, the transitaire to get the Moroccan rugs back to Toronto. The rugs need to get to Toronto. I need to get to Toronto.

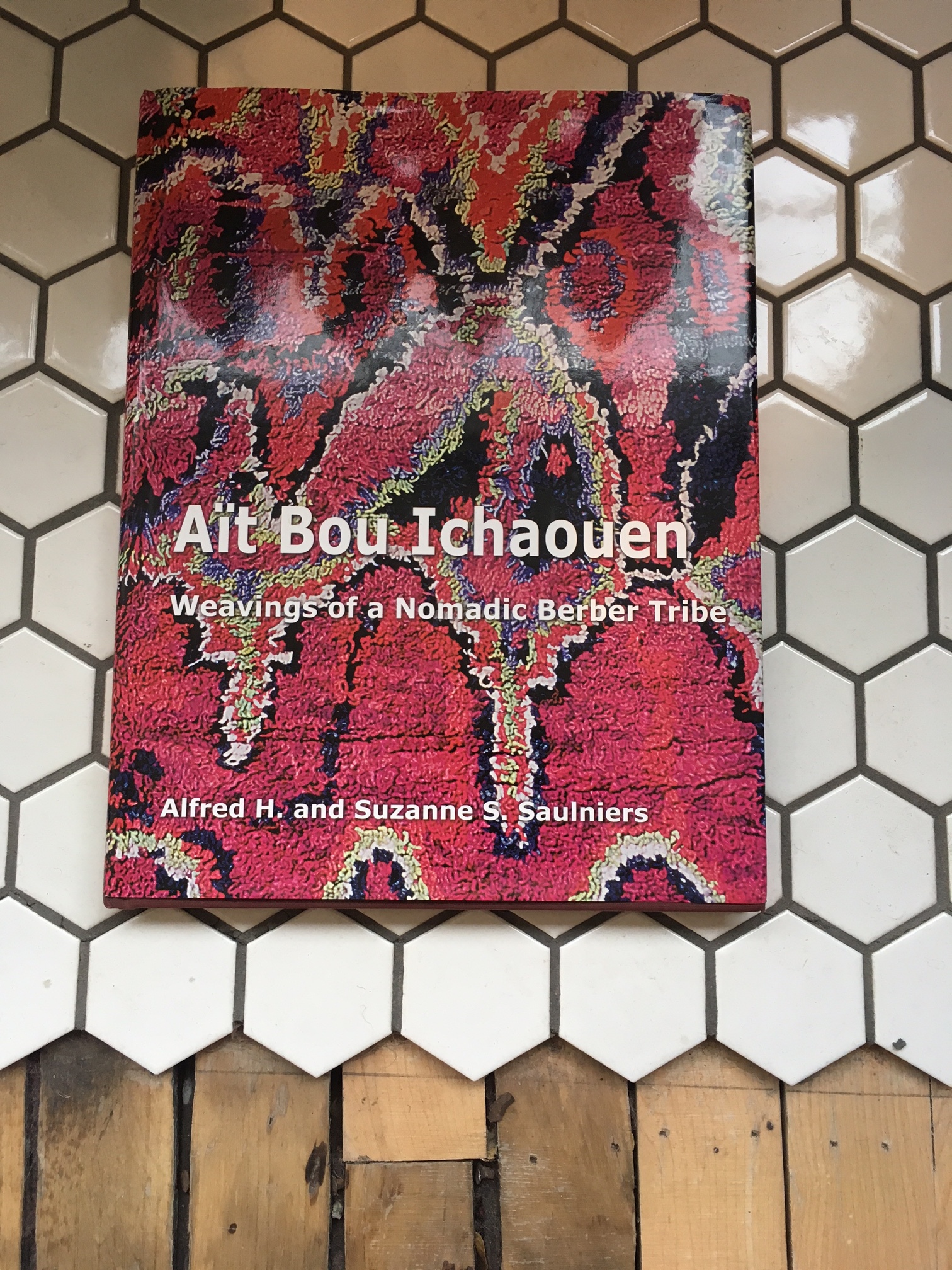

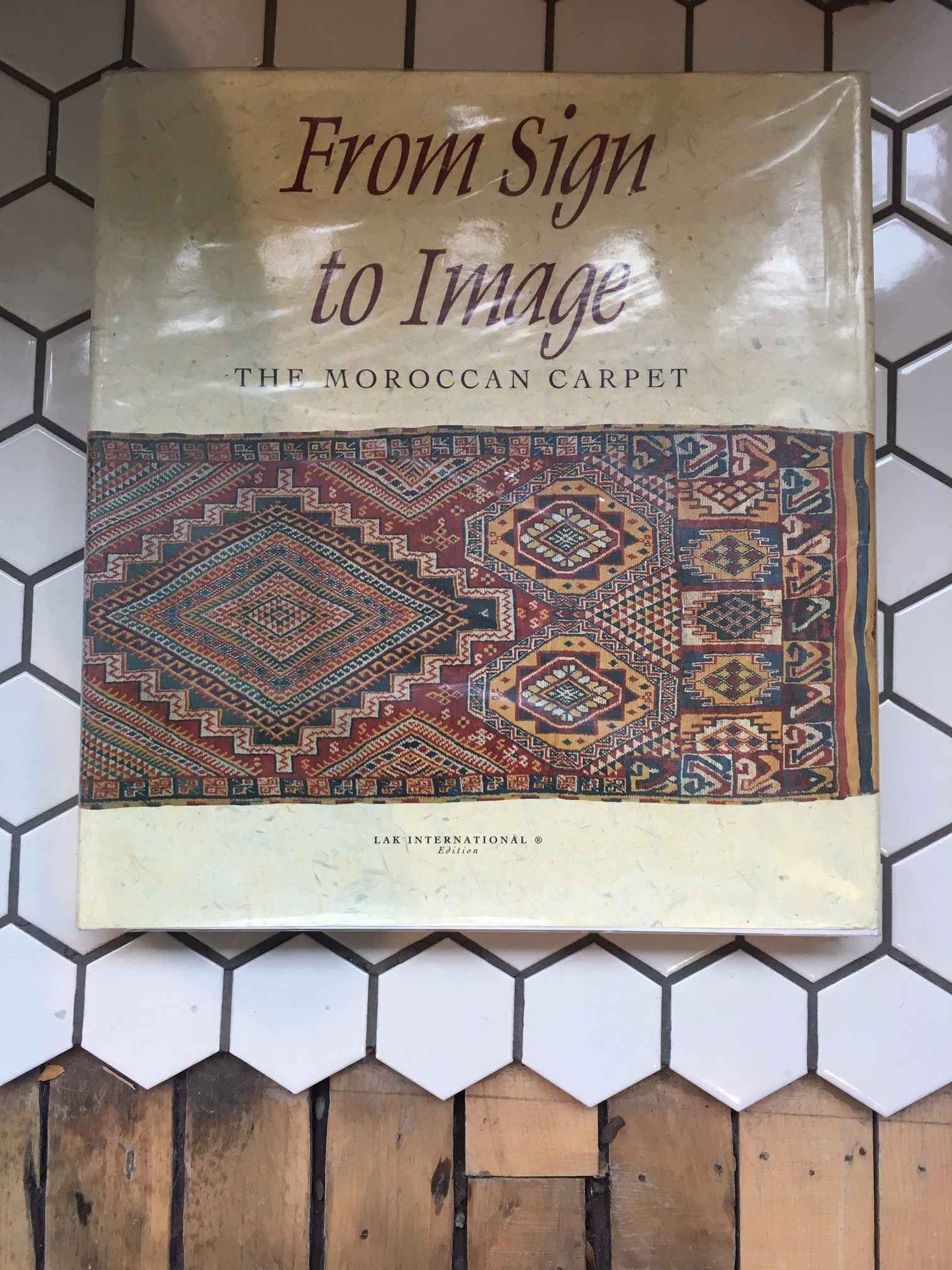

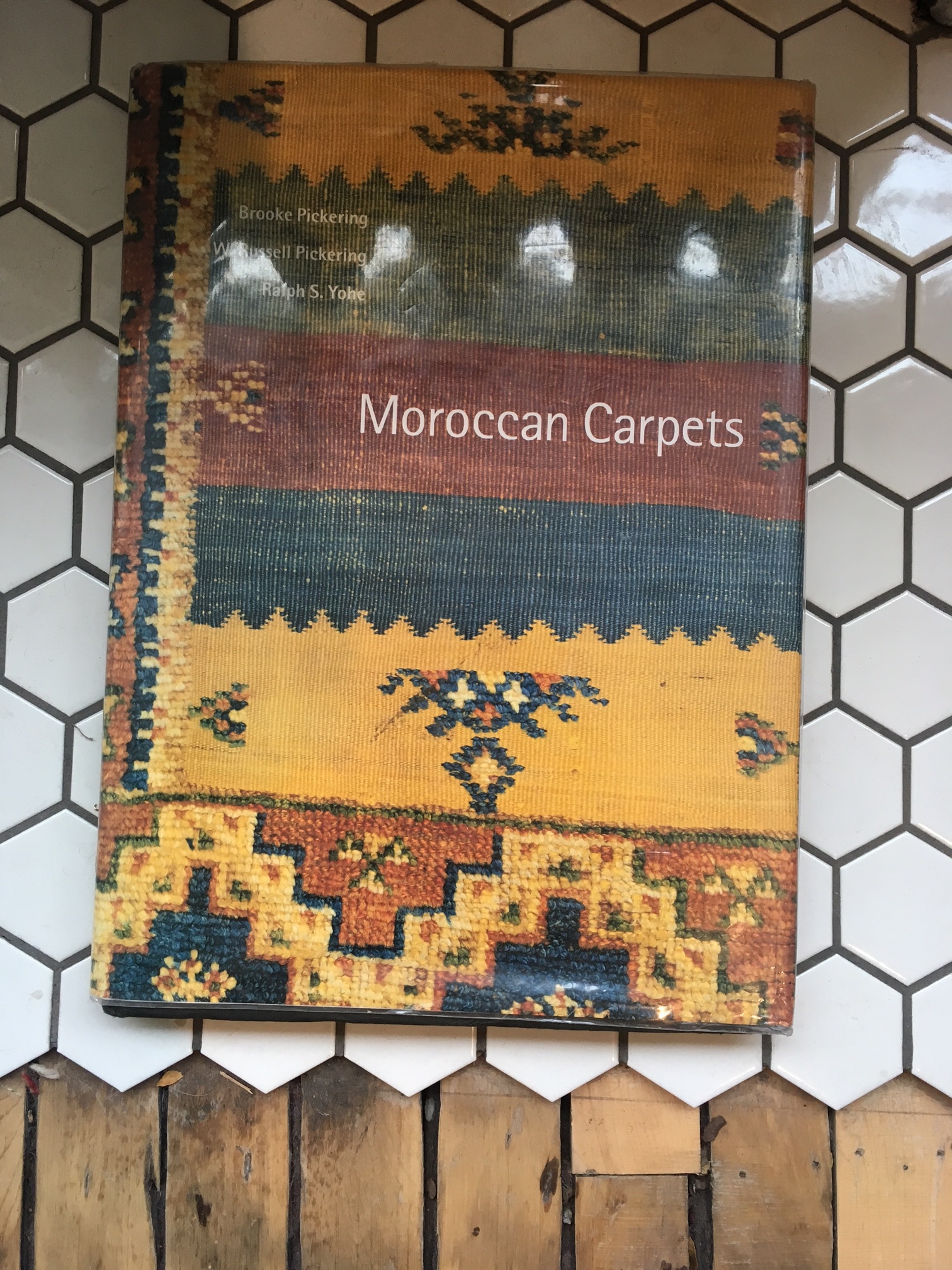

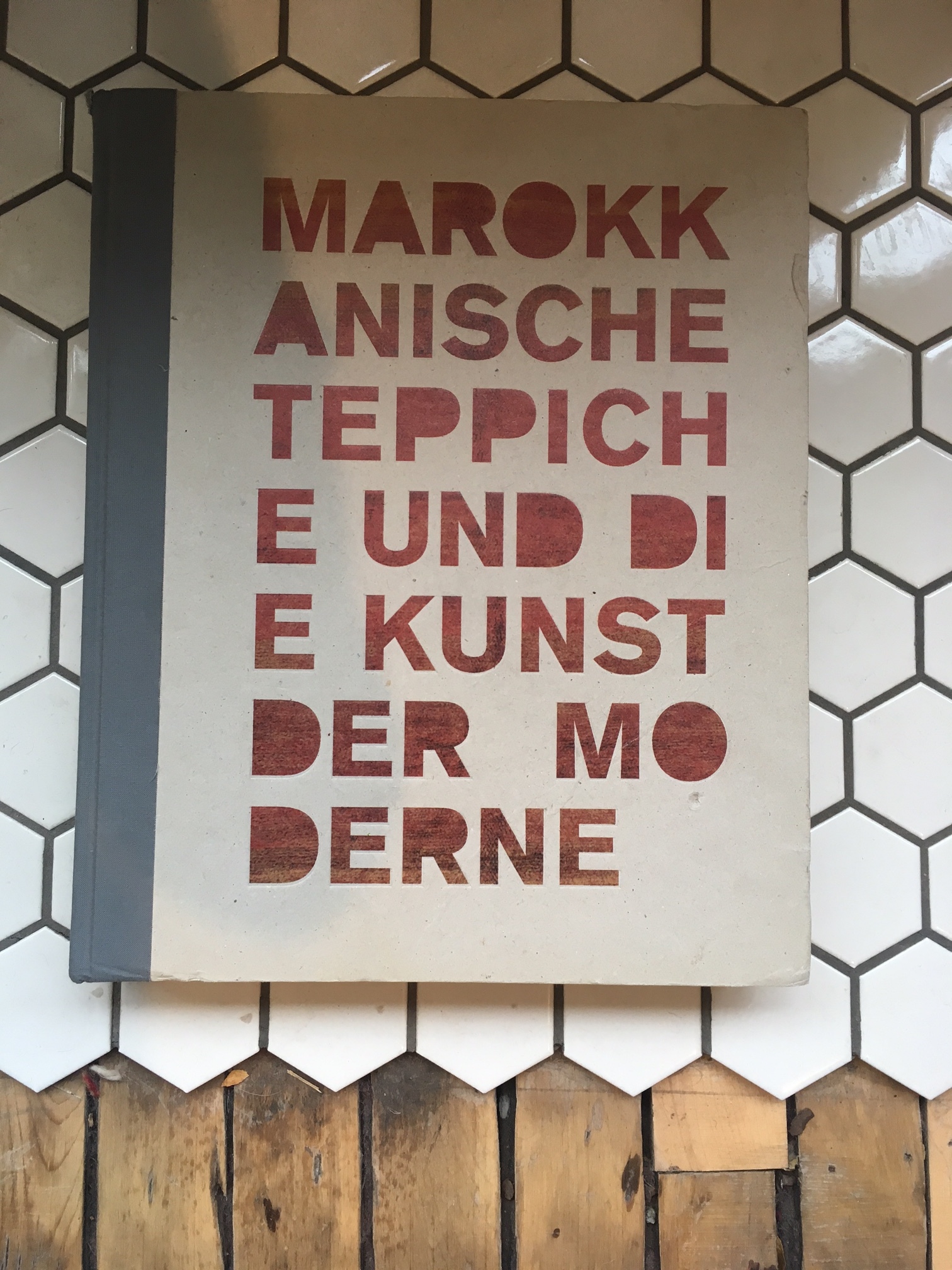

Marrakesh is sunny and festive feeling. Many people are returning to the hometowns and villages for the holiday, so the roads leaving town are busy. Eid is a holiday taken seriously, and many shops and businesses are closed, which feels very strange in Marrakesh—a busy and commerce-driven city. We stop by Mustapha's mother's apartment so he can deliver her some fruit he bought at a roadside stand. When he returns, we have lunch at a hotel where his brother works. We make it back to Mustapha's apartment in the Gueliz and his houseman goes to the Carrefour to buy us some beer. We spend the rest of the afternoon hanging out and looking through German language books about Berber weaving.

That night we meet a few of Mustapha's friends at a Tapas bar in the Hivernage, a fancy and Europeanized neighborhood between the Gueliz and the Medina. Mustapha's Scottish-Moroccan cousin and and his Bulgarian lounge-singer girlfriend suggest we go to a club a little outside of town. The bouncers let us in. We secure a table and order bottle service. I see Choukri's two boys, the students at University of Ottawa, at a table with a large group of girls. They are mortified to see Mustapha, who is in his mid forties, and try to hide from us. Mustapha—who knows no shame—rushes over to their table to greet them. We tire of the club and drive home on an empty tank of gas.

Da Club.

Choukri calls me the next day to inspect the vintage Moroccan rugs he has repaired. One of his m'taalams picks me up at Mustapha's apartment on a tiny motorbike. He has a helmet for himself but not for me. There is nowhere to hang onto the bike, so I hold him around his waist. It is now the day before Eid and Marrakesh is a ghost town. Choukri shows me the repaired rugs and all looks satisfactory. We shake hands, and the Moroccan rugs are packed. He sends his men home for the holiday and we say goodbye. He promises to come to Toronto and visit the shop in the spring. The m'taalam takes me back to Mustapha's. It is my last night, and we go to Mamma Mia, an Italian restaurant at which Mustapha is a regular. He speaks to the host in perfect Italian, and we are seated at his regular table in the back. We eat pasta, drink La Cuvée du Terroir, and talk about our plans for the next day. I have booked a hotel at the Casablanca airport, where I have a flight leaving for Montreal early the following morning. He has kept the rental car and will drive me the two hours to Casablanca. I offer to take the train, telling him he has been so generous and it is not necessary, but he insists.

Choukri's son comes by the apartment in the morning. He will be joining us on the drive. We get on the toll road north to Casablanca and listen to loud techno music the whole way. We get off the highway and again I must stop at an ATM to give Mustapha more cash for a few additional rugs I selected from his personal collection. We try a few before we find one that will let me withdraw money; I get the feeling Mustapha thinks I am trying to pull a fast one on him. I finally get the money and give it to Mustapha. We arrive at the airport hotel in Casablanca, give each other a hug and kisses on each cheek. We say long goodbyes, talking of future plans for Mustapha to come to Toronto in the spring and do a Berber art exhibition at Mellah. I smile when I imagine him speaking in his German/Moroccan accent, passionately presenting his unique Moroccan treasures with equal measures scholarship and shenanigans. Mustapha has treated me well—as a business partner and as a friend—and I am grateful.

For the first time in two weeks, I am alone. Mustapha's apartment didn't have a shower. Not because Mustapha is poor (he isn't), rather because he is both bohemian and lazy and doesn't own a shower head. You have to dump buckets of cold water on your head and body while trying to soap up. It's tricky and not very effective. I linger in the hot shower, get out and watch French TV in the air-conditioned room with a towel around my waist. I start to get hungry for dinner, so I get dressed and realize that I am missing my wallet. I ransack my luggage but cannot find it.I have 100 dirhams, which is enough for dinner, but not enough to get me from Montreal to Toronto after the flight. Panicking, I pick up the phone and call the one person I know: Daddy. Mustapha picks up on the first ring. He and Choukri's son are on the road back to Marrakesh. I left my wallet in the back seat after going to one of the many ATMs to pay Mustapha. He quickly devises a plan whereby he will send a man in a car the next morning at 6:30, the day of Eid, and a scant one hour before I have to be at the airport to catch my flight to Montreal. Mustapha, in one final act of kindness, will pay. I don't sleep well. I go down to the lobby at 6:15 and the man with my wallet is already there. He is friendly but does not speak English or French, so it is hard to convey how thankful I am. I offer him the 50 dirhams I have left, which he declines. I say shokran and Eid Mubarak. He smiles and walks away.

*****

It's easy when you work in the rug business to start thinking of rugs as inventory, as goods and chattels. You obsess over how many you have, how many you need, anticipating what people will want. You talk about them, you show them, you photograph them, you Instagram them, you unfold them and you fold them back up again. You get sick of some, you wonder why some aren't selling, you love your clients' taste, you hate your clients' taste, you hate your own taste. You try to sell the rugs, these handicrafts that have been labored over for months, family heirlooms that have been in homes for years, become mere things, commodities. You also can't go too far the other way and mystify them too much, orientalize them. They are made by other human beings, and they are beautiful, yes, but they are not magic. Berber rugs are proletarian, folk art. Artisans lacking formal technical skills weave them for practical reasons, made them the way the know how, and have been doing for thousands of years. It is we who imbue them monetary value. There is a lot of marketing malarkey around imported handicraft businesses, the social enterprise aspect of it, at least. Each object has a story, but often that story is that someone sold something in her home to buy cooking gas, or pay her cellphone bill, or to send her kid to school. Objects don't have stories. People have stories.